T.J. Power’s ‘DOSE Effect’ Review:

A closer look & ADHD critique

When T.J. Power is described as a “leading neuroscientist” and promises to revolutionise how we understand brain chemistry, it sounds VERY compelling. Especially if you’re struggling with ADHD, depression, or just trying to feel better, in a modern world that seems designed to drain your dopamine.

But if you’re someone who lives with ADHD or supports people who do, you need more than persuasive marketing. You need accuracy, humility, and genuine expertise. Unfortunately, “The Dose Effect” delivers pop-neuroscience-and-wellness (or as dressed up as cutting-edge neuroscience.

IAs a coach specialising in ADHD and evidence-based interventions, I take this seriously. When the people I work with are fed oversimplified solutions, they don’t just waste money – they are losing hope and self-belief.

That’s why I want to unpack the reality of the DOSE framework, examine what its claims actually mean, and explore why this represents a broader problem in how we approach mental health in the digital age.

1. Credential Inflation

Let’s start with who T.J. Power is, and what he isn’t.

Power graduated with a Master’s degree from the University of Exeter in 2020. His degree – in health science, neuroscience, sport psychology, and paediatrics – is a taught programme, not a research doctorate. That does NOT mean it’s worthless or ‘easy’ in any way, but it does mean that calling oneself a “leading neuroscientist” stretches the truth considerably.

In neuroscience, “scientist” usually implies years of research, a PhD, peer-reviewed publications, and a career spent generating new knowledge. Power frequently mentions published research – co-authored papers under the supervision of an established academic. That’s not unusual for a Master’s student, but it’s not the same as directing research programmes or advancing the field. And yet, on corporate websites and book jackets, the “leading neuroscientist” title is front and centre.

Why is this a problem?

Most people who describe themselves as neuroscientists typically hold PhDs

Power’s bio mentions “papers in the Journal of Cognition” which is technically true, but a little… economical. A closer look reveals he’s one of multiple authors on research led by an established academic who runs a university research lab, with another co-author who now has five peer-reviewed publications in ResearchGate alone.

Authority Transfer

The pattern continues in how Power’s roles are described. His LinkedIn lists short corporate training contracts – Pizza Hut Digital, Coca-Cola, and other well-known brands – framed as “neuroscientist” positions. To most people, that looks like research appointments. In reality, they’re corporate wellness workshops, closer to motivational speaking than scientific research.

Similarly, promotional materials highlight associations with Exeter University, the NHS, and Harrow School. Were these research posts? No – they were contracts to deliver training. That distinction matters. If you’ve ever been a guest lecturer, you’ll know it’s valuable experience – but not the same as holding a faculty role.

This blurring of lines is what I call credential inflation – making technically true statements sound like heavyweight authority. And when it comes to mental health, that inflation isn’t harmless – it shapes who people trust with life-impacting decisions.

Entrepreneurial Trajectory

This impressive trajectory – graduating in 2020, immediately launching a corporate training business, achieving “Sunday Times Bestseller” status, and building a social media following of 750,000 – follows a familiar pattern in the wellness – and coaching! – industry.

A Formula For a Best-selling Book on ‘Neuroscience’

- Get a relevant-sounding degree

- Create a catchy framework acronym (DOSE®)

- Position yourself as a leading expert

- Build a large social media following

- Convert those followers into customers

What’s missing? Years of research, peer review, clinical experience, or scientific contribution. I want to be clear that these aren’t always essential for effective coaching or training – but if you present yourself as a neuroscientist, they matter enormously.

2. A $95 Billion Corporate Wellness Mirage

Power’s work fits into the booming corporate wellness industry, projected to reach $94.6 billion by 2026. Companies, desperate to stem burnout and address mental health crises, are investing heavily in resilience training, mindfulness workshops, and productivity seminars.

But here’s what the research actually shows about these interventions:

According to Guardian reporting on an Oxford University comprehensive study in 2024 examining workplace wellness interventions, “almost none of these interventions had any statistically significant impact on worker wellbeing or job satisfaction.”

Even worse: “In some cases, wellbeing interventions seemed to make matters worse. For instance, workplace resilience and mindfulness training had a slightly negative impact on employees’ self-rated mental health.“

Research led by Jeffrey Pfeffer at Stanford University found that workplace stressors cause approximately 120,000 deaths annually and drive $175-280 billion in healthcare spending – but companies keep investing in superficial wellness programs rather than addressing root causes like toxic management, impossible workloads, or lack of genuine work-life balance.

Corporate Wellness in Numbers

The ADHD Connection

This matters for people with ADHD because:

– Generic wellness programs often ignore or downplay neurological differences

– “Resilience training” can be particularly harmful for those already struggling with executive function

– Real accommodation needs get buried under feel-good initiatives that don’t address structural barriers

– The focus on individual ‘wellness’ hides systemic workplace problems that disproportionately affect neurodivergent employees

When someone like Power promises to “rebalance brain chemistry,” he’s selling the same approach as countless corporate wellness providers – but dressed up with more technical, neuroscientific-sounding terms.

3. The DOSE Framework: What the Documents Reveal

The DOSE Lab has made two key documents public: their Intervention Mapping (April 2025) and their Research Proposal (March 2025). These documents reveal both the programme’s structure and its significant methodological limitations.

What DOSE Is Measuring

This looks more sophisticated than most wellness programmes – structured, theory-driven, with at least some intent to evaluate outcomes. It’s described as looking at ‘potential effects’ rather than ‘definitive conclusions’ but will that be noted if any statistical improvements are used in publicity? (See Red Flag section).

Critical Design Flaws

No Control Groups – The most fundamental flaw in the DOSE research is the complete absence of control groups.

This isn’t a minor issue -it significantly diminishes the credibility of results. Without control groups, you cannot distinguish between:

- Actual intervention effects

- Placebo effects (people feeling better because they expect to)

- Natural improvement over time

- Regression to the mean

- Seasonal variations in mood and energy

The Accenture case study claiming “+50% improvement in healthy phone usage” becomes scientifically worthless without knowing what happened to similar employees who didn’t receive the intervention.

The “academic partnership” with Southampton University isn’t independent research – it’s Power’s own employees studying their own product. The research proposal explicitly states it’s funded and conducted by Neurify staff, including Power himself and they are taking steps to make this clear to participants and make raw data available afterwards. However, this creates an enormous conflict of interest which might disqualify the research from a legitimate peer-review process.

It’s hard to get funding for real academic research which requires independence to prevent exactly this kind of bias. When the people conducting the study have a financial stake in positive results, the research is at risk of being read as marketing disguised as science.

Biological Claims vs. Behavioural Measures

DOSE claims to “rebalance brain chemistry” and “increase dopamine levels,” but no neurotransmitters are objectively measured. What they collect are subjective surveys about motivation and mood, not blood assays, cerebrospinal fluid analysis, or brain imaging.

This disconnect between claims and measurements is a hallmark of pseudoscientific approaches that appropriate scientific language without scientific rigour.

While DOSE is not just pseudoscience – it incorporates legitimate behavioural change principles – its scientific claims far outrun its data.

4. Oversimplifying Brain Chemistry

The central premise of DOSE – that balancing dopamine, oxytocin, serotonin, and endorphins will transform your mental health – sounds scientifically grounded and is seductively simple. Of course, it oversimplifies a very complex reality.

The Genetic Reality of ADHD

Research shows that ADHD involves many genetic variations affecting neurotransmitter function:

Some genetic variations in ADHD

DAT1 gene variants affect dopamine transporter efficiency, meaning some people literally process dopamine differently at the cellular level. The same “dopamine-boosting” activity that helps one person might have minimal effect on someone with different DAT1 variants.

DRD4 receptor variations alter how individuals respond to dopamine, explaining why the same intervention can work dramatically for one person and fail completely for another. This isn’t about motivation or compliance – it’s about fundamental differences in neural receptor sensitivity.

COMT gene polymorphisms influence how quickly dopamine is broken down in the prefrontal cortex. Some people clear dopamine rapidly and may benefit from frequent “dopamine hits,” while others process it slowly and might become overstimulated by the same interventions..

When you reduce these complex neurological differences to “just balance your brain chemistry,” you’re essentially telling people their struggles are lifestyle problems. This is particularly damaging for ADHD adults who’ve spent years being told they just need to “try harder” – when their genetics literally require different approaches.

Hormonal Complexity of Midlife

Consider women going through perimenopause, who experience unpredictable fluctuations not just estrogen but also serotonin, oxytocin and affects the behaviours that can release endorphins. These changes often precipitate a midlife ADHD diagnosis as hormonal support for executive function diminishes.

The research shows this isn’t simple: estrogen affects serotonin synthesis, dopamine receptor sensitivity, and oxytocin production through complex feedback loops that science is still working to understand. Reducing this to “take more cold showers for more dopamine” trivialises biology so profound it can alter personality, cognition, and long-term health risk.

Dr Feldman Barrett on Constructed Emotion

Dr. Lisa Feldman Barrett has written extensively on why the “chemical balance” metaphor is fundamentally misleading. As she explains, the brain isn’t a “chemical soup” waiting to be topped up – it’s a prediction machine constantly constructing reality through complex networks of interoception, experience, and environmental input.

Barrett’s research on constructed emotion shows that your brain’s construction of reality is unique to your individual wiring, experiences, and genetic makeup. She doesn’t promise universal solutions because legitimate neuroscientists understand the brain is far too complex for one-size-fits-all interventions.

That complexity is why simplistic “balance your four happy chemicals” stories do more harm than good – they imply that if you still struggle after following the protocol, you must be failing at the method rather than the method failing you.

5. Research Red Flags and Ethical Concerns

Several elements of DOSE’s approach raise serious ethical concerns about the exploitation of vulnerable populations.

The Online “Assessment” The privacy policy reveals they collect user data through an online quiz that claims to measure “personalised reports about your dopamine, oxytocin, serotonin, and endorphin levels.”

This is scientifically impossible. Neurotransmitters:

– Cannot be measured through questionnaires

– Require specialised brain imaging or invasive procedures to assess

– Fluctuate constantly throughout the day based on numerous factors

– Interact in complex ways that make isolated measurements meaningless

Data Exploitation The same privacy policy reveals this information is used for “internal research and product development.” Vulnerable people struggling with mental health think they’re being assessed scientifically when they’re actually providing marketing data for a corporate wellness business.

This illustrates one of the harms of credential inflation: people think they’re accessing legitimate neuroscience when they’re actually participating in data collection and product development for someone with a recent Master’s degree running corporate training workshops

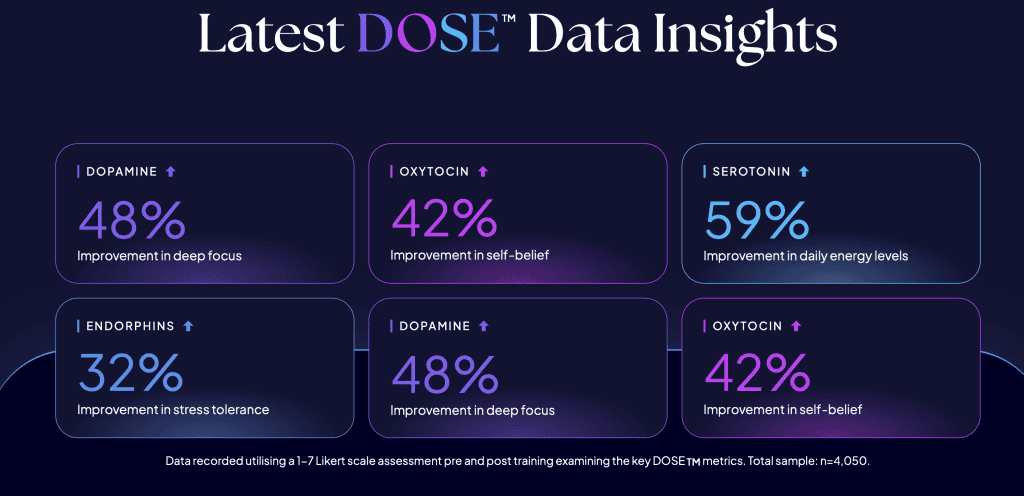

Exhibit A: The “Latest DOSE Data Insights”

Power’s website features a slick infographic claiming dramatic improvements across neurotransmitter levels based on a sample of 4,050 people. The presentation is designed to look scientifically impressive, but examining it closely reveals multiple red flags:

Impossible Neurotransmitter Measurement

The graphic explicitly labels improvements as being in “DOPAMINE,” “OXYTOCIN,” “SEROTONIN,” and “ENDORPHINS” – but the actual measures are subjective self-reports about “deep focus,” “self-belief,” and “energy levels.” You cannot measure neurotransmitters with Likert scales, yet the presentation deliberately conflates the two.

Missing Methodology

Despite claiming data from 4,050 people, there’s no information about:

– When this data was collected

– What the actual survey questions were

– Whether there was a control group

– The time interval between measurements

– Who conducted the research

– Any follow-up data

Suspiciously Round Numbers

48%, 42%, 59%, 32% – these remarkably clean percentages are unusual for legitimate research data, which typically produces messier numbers.

No Statistical Rigour

No confidence intervals, effect sizes, or significance testing reported – just impressive-looking percentages designed for social media rather than scientific scrutiny.

This shows exactly how wellness companies use scientific-looking presentations to legitimise fundamentally unscientific claims.

6. The Attention Economy and Credential Inflation

Power’s trajectory illustrates what economist Kyla Scanlon calls the “Attention Singularity” – where attention directly creates wealth, wealth instantly creates power, and power captures more attention in an accelerating cycle.

As Scanlon warns: “When narrative production becomes more valuable than actual production, we risk creating a world where attention harvesting matters more than building things.”

The Attention Pipeline

2020: Master’s degree → “Leading neuroscientist” narrative 2021-22: Corporate training contracts → Social media credibility 2023-24: 750k followers → Bestselling book status 2025: Book success → More corporate contracts and academic “partnerships”

Each cycle reinforces the next, regardless of actual experience or measurable impact. In an attention economy, people like Power and many other popular online experts are the inevitable outcome of a system that rewards confident over-simplification over years of expertise.

It’s a Systemic, Not Personal Problem

When capturing eyeballs becomes more valuable than hard-won expertise, credential inflation becomes a really profitable strategy. The attention economy incentivises exactly the opposite of what vulnerable populations need:

– Confident assertions over careful uncertainty

– Simple solutions over complex realities

– Viral engagement over evidence-based practice

– Charismatic personalities over rigorous methodology

Why This Matters for ADHD

People looking for legitimate “brain-based” support get easily caught in this system. They think they’re accessing cutting-edge neuroscience when they’re actually consuming attention-optimised content designed for engagement.

The attention economy systematically filters out the kind of careful, individualised, nuanced information that ADHD brains really need – because complexity doesn’t go viral, uncertainty doesn’t get shares, and “it depends on your individual circumstances” doesn’t sell millions of books.

7. Why This Matters for People with ADHD

If you’ve lived with ADHD, you know the exhaustion of trying system after system. You’ve probably been told you’re lazy, or need more grit. You’ve bought self-help books, planners, productivity products, and listened to (many) podcasts.

So when someone promises to “rebalance your brain chemistry,” it sounds better than good – it sounds almost like salvation.

ADHD isn’t a lifestyle problem that ‘just’ needs lifestyle solutions.

It’s a neuro-developmental condition with genetic, hormonal, and environmental components that interact. It often means:

The Dangers of Oversimplification

When wellness entrepreneurs oversimplify complex conditions, it’s not just waste people’s time and money. They can contribute to :

– Delays to accessing evidence-based treatment

– Perpetuate the myth that ADHD is caused by “poor lifestyle choices”

– Deepen shame in people who can’t make those “simple solutions” work

– Hide the need for genuine accommodations and systemic changes

The worst part is that some people may experience temporary improvements from any structured intervention (Hawthorne effect, placebo response, regression to the mean), which is then used as “evidence” that the approach works universally.

8. What ADHD Brains Actually Need

So if you’re living with ADHD, you don’t need another guru promising simple solutions. You need:

ADHD? Look for

Real Expertise Acknowledges Uncertainty

For genuine neuroscience education that respects complexity, listen to:

Lisa Feldman Barrett’s work on predictive brain processing and individual differences in emotional construction

Dr. Russell Barkley’s research on ADHD genetics and why interventions must be individualised

Real experts don’t promise ‘easy’ or simple solutions because they understand the brain is far too complex for one-size-fits-all interventions. They acknowledge what we don’t know, respect individual differences, and focus on what actually helps rather than what sells.

9. Conclusion: Your Brain Deserves Better

T.J. Power is energetic, engaging, and clearly passionate about wellbeing. His DOSE framework may inspire some people to reflect on their habits and make positive changes. The behavioural principles underlying the program have some merit, and for people with relatively straightforward wellness goals, it might provide helpful structure.

But calling it neuroscience is misleading. Positioning it as a solution for complex neurodevelopmental conditions is irresponsible. And using academic partnerships and corporate success to imply scientific validity crosses ethical lines.

When someone positions themselves as a “leading neuroscientist” without the years of research, clinical experience, and scientific humility that entails, they aren’t serving vulnerable people.

They’re selling hope in a lab coat while contributing to a system that prioritises attention capture over genuine expertise.

The broader problem is NOT T.J. Power – it’s an entire economic system that rewards confident oversimplification while marginalising the careful, uncertain, individualised work that complex conditions actually require.

ADHD brains deserve better than that.

Your brain isn’t broken, and you don’t need to “rebalance” your neurotransmitters – you need support that actually fits your neurology, respects scientific complexity, and acknowledges what we don’t yet know about the brain.

Real expertise comes with growing humility about how much we still don’t understand. In a world drowning in oversimplified solutions, that awareness is exactly what we need.

Methodology Note: This analysis is based on publicly available documents including DOSE Lab’s Intervention Mapping (April 2025), Research Proposal (March 2025), Privacy Policy, promotional materials, and Power’s professional profiles, accessed September 2025.

Sources and References

Research Studies and Academic Papers

Barrett, L. F. (2017). The theory of constructed emotion: an active inference account of interoception and categorization. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 12(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsw154

Dunietz, G. L., Tittle, L. J., Mumford, S. L., O’Brien, L. M., Baylin, A., Schisterman, E. F., Chervin, R. D., & Young, L. J. (2024). Oxytocin and women’s health in midlife. Journal of Endocrinology, 262(1), e230396. https://doi.org/10.1530/JOE-23-0396

Goh, J., Pfeffer, J., & Zenios, S. A. (2015). The Relationship Between Workplace Stressors and Mortality and Health Costs in the United States. Management Science, 62(2), 608-628. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2014.2115

Le Moëne, O., Stavarache, M., Ogawa, S., Musatov, S., & Ågmo, A. (2019). Estrogen receptors α and β in the central amygdala and the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus: Sociosexual behaviors, fear and arousal in female rats during emotionally challenging events. Behavioural Brain Research, 367, 128-142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2019.03.045

McCarthy, M., & Raval, A. P. (2020). The peri-menopause in a woman’s life: a systemic inflammatory phase that enables later neurodegenerative disease. Journal of Neuroinflammation, 17, 317. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-020-01998-9

Rybaczyk, L. A., Bashaw, M. J., Pathak, D. R., Moody, S. M., Gilders, R. M., & Holzschu, D. L. (2005). An overlooked connection: serotonergic mediation of estrogen-related physiology and pathology. BMC Women’s Health, 5, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-5-12

Expert Resources and Factsheets

Barkley, R. A. (2017). What Causes ADHD? Russell Barkley Factsheet. https://www.russellbarkley.org/factsheets/WhatCausesADHD2017.pdf

Nadeau, K. (2024, June). ADHD in Adults at Midlife. Interviewed by Susan Buningh. Attention Magazine. https://chadd.org/attention-article/adhd-in-adults-at-midlife/

News Articles and Commentary

Berger, K. (2017, March 30). Ingenious: Lisa Feldman Barrett – Inside a new theory of emotions that spotlights how the brain works. Nautilus. https://nautil.us/ingenious-lisa-feldman-barrett-236538/

Guardian. (2024, January 17). Work wellness programmes don’t make employees happier – but I know what does. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/jan/17/work-wellness-programmes-dont-make-employees-happier-but-i-know-what-does

Audio and Multimedia

Scanlon, K. (2023). The Attention Economy and Young People. Prof Galloway. Read by George Hahn. https://www.profgalloway.com/the-attention-economy-and-young-people/

DOSE Lab Resources

DOSE Lab. (2025, April). Intervention Mapping. https://thedoselab.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/DOSE-Intervention-Mapping-1.pdf

DOSE Lab. (2025, March). Research Proposal. https://thedoselab.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/DOSE-Dopamine-Research-Proposal-01-03-25.pdf

DOSE Lab. (2025). Privacy Policy. https://thedoselab.com/privacy-policy/

DOSE Lab. (2025). Homepage. https://thedoselab.com

Additional Expert Resources

Barrett, L. F. Personal website. https://lisafeldmanbarrett.com